Topics Covered in this Section

20.7.1 An Introduction to a Conceptual Production Model for the Peccary

20.7.2 Concepts in Developing an Intensive Animal Production Model for the Collared Peccary

[I] The Objectives of the Peccary Production System

[II] The Life Cycle of the Peccary

[III] The Physiological States of the Quenk/Peccary

[IV] Target Performance Coefficients for the Quenk or Collared Peccary

[VI] Animal Specific Needs as influenced by the Factors affecting animal Production Needs

20.7.4 Background to the Peccary Production Model

AGLS 6502 Lecture 20.7 - The Javelina or Quenk:

Conceptual Production Model for the Peccary

20.7.1 An Introduction to a Conceptual Production Model for the Peccary

The collared peccary (T. tajacu) is an indigenous wildlife species to the neo-tropics, including Trinidad. The animal is being viewed as a candidate for rearing under captive intensive/semi-intensive conditions as a new livestock species for domestication.

Aim :

- To provide a feeding programme for the collared peccary. Nutrition and Feeding

- To formulate a breeding programme for the collared peccary. Breeding and Reproduction

- To design a housing system for the collared peccary in confinement. Housing and Environment

- To provide measures for eliminating factors/elements that contribute to mortality and morbidity. Health and Disease

- Demonstrate the economics of a production system for the collared peccary. Economic Parameter

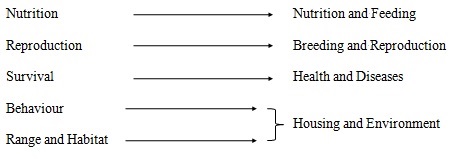

To formulate a production model, the biological factors determined earlier are to be translated into livestock production parameters:

Socio-economic considerations are a key ingredient when translating a natural science into a production science. Each of the above four (4) factors will have economic implications. Likewise, the biological factor, behaviour, is a limiting factor common to all components of production.

back to top20.7.2 Concepts in Developing an Intensive Animal Production Model for the Collared Peccary

[I] The Objectives of the Peccary Production System

In order to develop your Peccary production system you must first begin with the end in mind, i.e. what are the objectives of your production system and what products or animals are you going to sell. This would determine what you do.

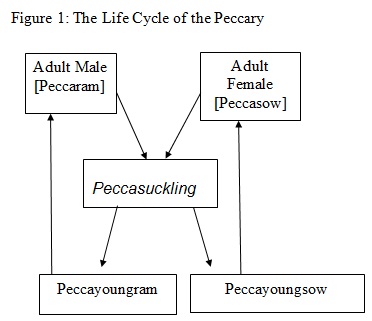

[II] The Life Cycle of the Peccary

Figure 1: The Life Cycle of the Peccary

[III] The Physiological States of the Quenk/Peccary

- Breeding Females [Peccasow]

- Breeding Males [Peccaram]

- Suckling Young Peccary [Peccasuckling]

- Young Growing Post Weaning but Sexually Immature Females [Peccayounsow]

- Young Growing Post Weaning but Sexually Immature Males [Peccayoungram]

- Sexually Mature Females [Replacement Peccasow]

- Sexually Mature Males [Replacement Peccaram]

[IV] Target Performance Coefficients for the Quenk or Collared Peccary

| Table 4: Target Performance Coefficients for the Quenk or Collared Peccary | |||

| Characteristic | Parameter | ||

| Age of Sexual Maturity | 8-14 months | ||

| Age at First Litter | 13-15 months | ||

| Breeding | Year round | ||

| Length of Gestation | 140-158 days | ||

| Return to estrus after parturition, if the offspring dies | |||

| Lactational anoestrous | Yes | ||

| Length of Oestrous Cycle | 22.6 – 34.0 days | ||

| Duration of Estrus | 3.4 –4.8 days | ||

| Signs of Estrus | See note under breeding | ||

| Number of Offspring per Litter (litter size) | 1- 4 | ||

| Minimum Number of Litters per Year per Female | 1.25 (range 1-3) | ||

| Number of days between successive parturition (parturition interval) |

181– 195 days | ||

| Birth Weights: Male Female |

g g |

||

| Average | 623 g [0.6kg] | ||

| Birth Lengths : Male Female |

cm cm |

||

| Weaning Age | 4 days to 8 weeks | ||

| Weaning to Conception | 3-17 days | ||

| Weight of Mature Male | 21.1kg | ||

| Weight of Mature Female | 19.0kg | ||

| Weaning Weight: Male Female |

g g |

||

| Weaning Length Male Female |

cm cm |

||

| Mortality Rate: Offspring | % | ||

| Mature Agoutis | % | ||

[VI] Animal Specific Needs as influenced by the Factors affecting animal Production Needs

a. Housing and Environment Objectives:

- To maximize the use of space for the production of a herd of collared peccary.

- To provide an environment for production that limits stress and as near as possible, meet the needs of the animal.

- To provide an environment for maximum contact between animals and the ‘farmer’.

Features of Housing for Peccaries The housing for the peccaries must first take into consideration the unique animal behavior of these animals.

The important points to note are as follows:

1] the peccary has two pairs of sharp canine teeth;

2] the peccary is a highly social animal, it does not like any new animals entering the group;

3] it does not have any unique environmental requirements, except that family groups must be kept separated;

4] four foot [about 1.25 meters] high enclosures should be suitable;

5] the animals must not be able to put their head or mouth outside the enclosures or they could damage the stockmen by biting with their sharp teeth.

The housing has to be designed in relation to the existing life cycle stages in the production system for the collard peccary. Accommodation can be provided in an intensive system where maximum contact is anticipated between the ‘farmer’ and the animals.

The system design is as follows:

Enclosure Size -

9m x 10.5 m = 945 m2

Capacity -

(i) Breeding males = 2

(ii) Breeding females = 6

(iii) Post-weaner/Growers = 12

(iv) Finishers = 12

Detail of Compartments -

(i) Breeding males:

- area 2m x 9m (18 m2)

- partially paved and covered. This area is 2m x 2m

- circular enclosed area within paved area 3 m diameter (to serve as an introduction area for new stock)

(ii) Maternity Pens:

- capacity for six (6) females

- area 2m x 9m (18 m2) and density of 3 m3/head

- individual pens 1.5m x 2m (3 m2)

- two gates to provide a restraining area

- two service gates

- wind break area 0.66m x 0.66m for protection of female and young peccers

- pens are completely covered and paved

- drains into a central outlet

- rear wall 0.66 m high

- border 1 block (20 cm) in height and chain link wire to a height of 2 m. There is no need to maintain contact between females, but it is necessary between males.

(iii) Post-Weaner/Grower (3 days - 24 weeks):

- area 2.5m x 9m (22.5 m2)

- four (4) 2m gates to form a restraining area

- paved and covered area 2m x 3m

- watering and feeding areas are positioned where they will not hamper gate use.

(iv) Finisher (24 weeks - 40 weeks):

- area 4m x 9m (36 m2)

- system of four (4) 3m gates to assist in restraining

- covered and paved area 4m x 3m

The entire enclosure is to be fenced with chain link wire, embedded in concrete. This is to prevent the peccaries from burrowing under the fence. The fence need not be more than six feet in height. The covered areas could be constructed following those conditions specified for the domestic pig (2.4 - 3m at the highest point, and 1.8 - 2.2 m at the eaves).

The chain link wire utilized, will allow the free flow of air currents throughout the structure. Wind breaks are provided in the maternity area and post-weaner areas. The use of chain link wire also serves to allow continued contact between males and females. Water and trough requirements will follow those specified for the domestic pig.

Spacing requirements used are based on recommendations determined in section 4.0. In comparison, housing for the domestic pig, is much smaller in dimension and in relation to body size/unit space. There is therefore the potential for increasing the stocking density for a given space.

As advised for domestic pig production, individual pens have been used as maternity pens, the equivalent to the farrowing pens of the domestic pig. The use of a pallet and bedding straw may be necessary to provide a dry area within the maternity pen in the vicinity of the wind break.

Objectives:

- To formulate feeding programmes for the collared peccary, taking into consideration the requirements at varying physiological stages. The domestic (Sus scrofa) will be used as a parallel species.

- To grow out captive reared collared peccaries to market weight for meat.

The collared peccary in Charles (1997) and the white lipped peccary in Fradrich (1995), have been demonstrated to be effectively maintained on a diet of fruits, roots, green plant material, and a minimum quantity of animal protein. In attempting to determine the requirements of the collared peccary, a review of the literature showed a closer relationship to the monogastric domestic pig (Shilvey et al., 1985). This view was possibly more in relation to the use of energy feeds.

When assessing the protein requirements of the animal, Carl and Brown (1985) felt that there was an inclination more towards that of ruminants. Similarly, such ruminant-like behaviour was assumed to occur in relation to the synthesis of vitamins (Lochmiller et al., 1987).

There is an apparent need for further research on the digestive physiology of the collared peccary. These research programmes should aim at such subjects like the extent of the contribution of VFAs. The possibility of the use of non-protein nitrogen (NPN) in the diet. Note has been made of the fact that no mention has been made of the level of ammonia production from microbial degradation of protein in the peccary’s stomach. Ammonia in the rumen liquor is the key intermediate in the microbial degradation and synthesis of protein (Mc Donald et al., 1982).

The level of protein in the diet has an effect on the growth of rumen organisms. A consequence of a low protein diet is a retardation of the breakdown of carbohydrates by microbes (Mc Donald et al., 1982). It is suggested that the of the collared peccary in captivity be based on the use of cheaper and available fruits, roots and nuts. These have been shown to have success in captive holdings. The supplemental use of commercial feed is also suggested. Comparative work on the use of the two feeds are an advantage in determining the level of goal realization each allows.

Table 3. Suggested Nutrient Profile for the Collared Peccary

| Nutrient | Pregnancy | Lactation | Weaner - 24 weeks |

Fattener + 24 weeks |

Breeder |

| Digestible Energy (MJ/kg) | 12.5 | 12.5 | 14.8-13.8 | 12.5 | 12.5 |

| CP g/kg | 120-130 | 160-170 | 220-180 | 160-170 | 160-170 |

| Ca g/kg | 7.5 | 7.5 | 7.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 |

| P g/kg | 5.0 | 5.0 | 6.0 | 5.5 | 5.5 |

| Salt (NaCl) g/kg | 5.5 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| Fe mg/kg | 80.0 | 80.0 | 100 | 100-120 | 100-120 |

| Zn mg/kg | 50 | 50 | 100 | 100-150 | 100-150 |

| I mg/kg | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Se mg/kg | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Mn mg/kg | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Vitamin A (IU/kg) | 8000 | 6000 | 6000 | 4000 | 4000 |

| Vitamin D (IU/kg) | 2000 | 1500 | 1500 | 1000 | 1000 |

| Vitamin E (IU/kg) | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Riboflavin mg/kg | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| Panthotenic Acid mg/kg | 16.0 | 16.0 | 20 | 10 | 10 |

| Vitamin B12 mg/kg | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.018 | 0.010 | 0.010 |

| Biotin mg/kg | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 |

Utilizing extracts from nutrient tables for the domestic pig (Appendix II), a suggested diet profile has been presented (Table 10). The table shows five (5) physiological stages, suggesting possible requirements. These profiles are available in commercial pig rations.

back to topc. Health and Disease Management

Objective:

- To reduce the risk of diseases that arise under intensive (high population density) systems.

In the review of Sowls (1984) a comprehensive account has been provided of external and internal parasites and infections and diseases to which the peccary becomes predisposed. Included in his account, Sowls (1984) has also been able to review some diseases of the domestic pig to which the collared peccary can become susceptible.

The known adage “ and ounce of prevention is better than a pound of cure”, suits the peccary system quite well. To avoid pre-disposition to disease-causing organisms will serve to greatly reduce the potential for spread. Therefore, under high density production systems basic animal hygiene husbandry practices such as providing clean water, clean feeding utensils, frequent washing of pens, regular removal of faecal matter, all serve to ensure that pathogen loads are not built up.

Important practices also include providing the proper environment which as close as possible reflects the animal’s natural habitat, including atmospheric microclimate, housing space per animal. Procedures should also be familiar with the animals, and be able to detect changes in behavior that may be viewed as adversely uncharacteristic.

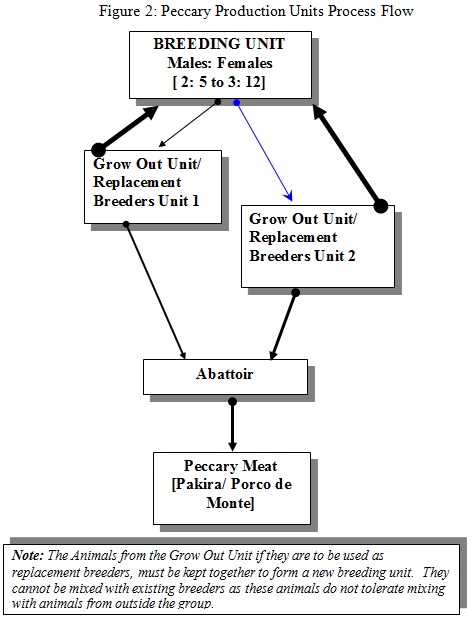

There are 4 main production units.

Unit 1:

Breeding Unit [Group Housing]

Breeding Females [Peccasow]

Breeding Males [Peccaram]

Suckling Young Peccary [Peccasuckling]

Ratio of Peccaram: Peccasow = 2: 5 to 3: 12

Note:

1] Because the Peccaries are very social animals which do not introduce strangers into the group, at least two (2) breeding males should be in the group in the event that something happens to one of the breeding males there is an automatic replacement already within.

2] Breeding males within a group do not compete aggressively as is seen with other species.

3] As Peccaries demonstrate lactational anoestrous it necessary to wean as early as possible [less than four weeks] to get the females back on heat and pregnant again.

Unit 2: Grow Out Unit/ Replacement Breeders Unit [Group Housing]

Young Growing Post Weaning but Sexually Immature Females [Peccayoungsow]

Young Growing Post Weaning but Sexually Immature Males [Peccayoungram]

Note:

1] This would consist of the weaned animals. As weaning could take place after one week or up to about four months, it would be necessary for us to determine up to what age young animals would tolerate new introductions into the group.

2] The majority of males from this group could be slaughtered at about six months. The larger and faster growing males should be kept with the females for reproduction.

3] It would be necessary to have at least two of these units. Since the Peccary would be expected to breed year round the young growing animals would have a six month spread.

Unit 3:

Grow Out Unit/ Replacement Breeders Unit [Group Housing]

Same as unit 2, but would contain the younger animals.

Unit 4: Utility Pen

Peccary Production Units Process Flow

Figure 2: Peccary Production Units Process Flow

20.7.3 Socio-economic Factors

The production of the collared peccary aims at satisfying the consumers with peccary meat. The peccary is grow out in 40 weeks after a gestation period of 146 days, from a neo-nate of 0.623 kg, to an approximate weight of 18 kg. Kiltie (1985), Bissonette (1982), and Nowak (1991), have all given accounts of the animal exceeding 25 kg live-weight. Based on records in Sowls (1984), the growth rate of the collared peccary has been calculated at 62g/day. A dressing percentage of 72.3 % (Sowls, 1984) (Table 5). The peccary is expected therefore to produce in a 40-week period, 13 kg of meat.

At a cost of TT $ 44/kg (Asibey, 1986), the carcass can be offered at a value of TT $ 572. The production model designed is therefore expected from six (6) breeding females to give from one cycle a value of $ 6,864 in sixty-one weeks - an estimated weekly earning of TT $ 113 from the enterprise, not considering the overhead costs.

Table 5: Growth Parameters for the Collared Peccary, Domestic Pig and Tropical Goat

| Characteristics | Collared Peccary | Domestic Pig | Goat |

| Body Length (cm) | 440 - 575 | ||

| Tail Length (cm) | < 2.54 | ||

| Mature Body Weight (male) | + 18 kg | + 100 | 60-80 kg |

| Mature Body Weight (female) | + 18 kg | + 100 | 40-60 kg |

| Birth Weight (kg) | 0.623 kg | 0.9 kg | 1-2 kg |

| Market Weight (kg) | 18 kg | 90 kg | 32 – 36 kg |

| Market Age (wk.) | 40 weeks | 22 – 26 weeks | 24 – 32 weeks |

| Carcass Dressing (%) | 72.3 % | 65-70 % | 40-45% |

| Growth Rate g/day | 62 g/day | 570 – 675 g/day | 50-200 g/day |

20.7.4 Background to the Peccary Production Model

The following experiences have demonstrated that Peccaries could be reared intensively and reproduce successfully in captivity:

- the experience of the Emperor Valley Zoo, the West Berlin Zoo, Zoo Zürich and many other Zoos;

- the experience of the Soucoumou Experimental Station in French Guyana;

- the work of Embrapa in Brazil;

- the work of Sergio Luiz Gama Nogueira Filho of the University of San Paulo and the Universidad Esdadual de Santa Cruz, Bahia, Brazil;

- the intensive backyard rearing experience of Desmond James in Mausica, Trinidad, Trinidad and Tobago.

20.8 References

- Anon (1970): World of Wildlife: Animal of South America. Orbis Publishing, London. 304 pp.

- Anon (1975): World of Wildlife: Animals of South America. Orbis Publishing, London. 304 pp.

- Anon (1991): Microlivestock: Little known small animals with a promising economic future. National Academic Press. Washington D.C. 449 pp.

- Asibey, E. (1986): Wildlife Farming in Trinidad and Tobago: Problems and Prospects. UNDP/FAO Field Document No. 5. Port of Spain. 75 pp.

- Bissonette, A. (1982): Collared Peccary (Dicotyles tajacu). In J.A. Chapman and G.A. Feldhamer eds. Wild Mammals of North America: Biology, Management and Economics. The John Hopkins University Press. Baltimore pp. 841-850

- Blankenship, H; Parker, S.C.; and Quortrup, Svend A. (1990): Game Cropping in East Africa: The Kekopey Experiment. The Texas Agricultural Experiment Station. Texas 128 pp.

- Byers, A. and Bekoff, M. (1981): Social, Spacing and Co-operative Behavior of the Collared Peccary (Tayassu tajacu). Journal of Mammalogy 12:4 pp. 767-785

- Carl, G.R. and Brown, R.D. (1983): Protozoa in the fore-stomach of the collared peccary (Tayassu tajacu). Journal of Mammalogy 64:4 pp. 709

- Carl, G.R. and Brown, R.D. (1985): Protein requirement of adult collared peccaries. Journal of Wildlife Management 49:2 pp. 351-355

- Charles (1997): Zookeeper, Emperor Valley Zoo. Personal Communication

- Comizzoli, P.; Peiniau, J.; Dutertre, C.; Planquette, P. and Aumaitre, A. (1997): Digestive utilization of concentrated and fibrous diets by two peccary species ( Tayassu peccari , Tayassu tajacu ) raised in French Guyana Journal Animal feed Science and Technology 64: 215-226

- Eisenberg, F. (1989): Mammals of the Neotropics: The northern neotropics. Vol. I. University of Chicago Press, USA. 449 pp.

- Emmons, L.H. (1990): Neotropical Forest Mammals: A field guide. University of Chicago Press, USA. 281 pp.

- Eusebio, J.A. (1980): Pig Production in the Tropics. Longman Group Ltd. Hong Kong. 115 pp.

- Freese, C.H. and Saavedra, C.J. (1991): Prospects for Wildlife Management in Latin America and the Caribbean. In J. Robinson and K.H. Redford eds. Neotropical Wildlife Use and Conservation. University of Chicago Press, USA. pp. 430 -444

- Herring, S.W. (1985): Morphological correlates of masticatory patterns in peccaries and pigs. Journal of Mammology 66:4. pp. 603-617

- Kiltie, R.A. (1981a): Stomach contents of rain forest peccaries (Tayassu tajacu and T. pecari). Biotropica 13:3. pp. 234-236

- Kiltie, R.A. (1981b): The function of interlocking canines in rain forest peccaries (Tayassuidae). Journal of Mammalogy 62:3. pp. 459-469

- Kiltie, R.A. (1982): Bite force as a basis for niche differentiation between rain forest peccaries (Tayassu tajacu and T. pecari). Biotropica 14:3 pg. 188-195

- Langer, P. (1979): Adaptation significance of the fore-stomach of the collared peccary, Dictoyles tajacu (L. 1758) (Mammalia: Artiodactyla). Mammalia 43:2, 235-245

- Lochmiller, R.L.; Hellgren, E.C. and Grant, W.E (1987): Influence of moderate nutritional stress during gestation on reproduction of collared peccaries (Tayassu tajacu). Journal of Zoology 211: 321-328

- Maton, A.; Daelemans, J. and Lambrecht, J. (1985): Housing of Animals: Construction and equipment of animal houses. Development in Agricultural Engineering 6. Elsevier, Amsterdam. 458 pp.

- Mc Donald, P.; Edwards, R.A. and Greenlagh, J.F.D. (1982): Animal Nutrition. English Language Book Society/Longman. England. 479 pp.

- Nowak, R.M. (1991): Walker’s Mammals of the World. 5th Edition. Vol. II. The John Hopkins University Press. London. pp. 1346-1347

- Oldenburg, W.; Ettestad, P.J.; Grant, W.E. and Davis, E. (1985): Size, overlap and temporal shifts of collared peccary herd territories in South Texas. Journal of Mammalogy 66:2. pp. 378-380

- Payne, W.J.A. (1990): An Introduction to Animal Husbandry in the Tropics. Longman, Singapore. 881 pp.

- Proverbs, G.A. (1989): Tropical Pig Production Handbook. CARDI Trinidad, W.I. 40 pp.

- Redford, K.H. and Robinson, J.G. (1991): Subsistence and Commercial use of wildlife in Latin America. In J. Robinson and K. Redford. Neotropical Wildlife Use and Conservation. University of Chicago Press, USA. pp. 6-23

- Robinson, J.G. and Eisenberg, J.F. (1985): Group size and foraging habits of the Collared Peccary (Tayassu tajacu). Journal of Mammalogy 66:1. pp. 153-155

- Shilvey, C.L.; Whiting, F.M.; Swingle, R.S.; Brown, W.H. and Sowls, L.K. (1985): Some aspects of the nutritional biology of the collared peccary. Journal of Wildlife Management 49: 729-732

- Simpson, C. D. (1984): Artiodactyls. In S. Anderson and J. Knox-Jones Jr. eds. Orders and Families of Recent Mammals of the World. John Wiley and Sons, USA. pp. 563-576

- Sowls, L.K. (1984): The Peccaries. The University of Arizona Press. Tucson, Arizona. 251 pp.

- Wong-Mottley, S. (1986): Housing of Pigs. Extension Fact Sheet. CAEX-FS/64/86. The University of the West Indies, Trinidad and Tobago. 2 pp

Helpful Links, Photos, Videos and Multimedia