Tropical Animal Science Integrated Network

3/9/2026 8:20:47 AM

Tropical Animal Science Integrated Network (TASIN)

A conceptual framework for the formation of a Tropical Animal Science Integrated Network (TASIN)

THE NEW HORIZONS

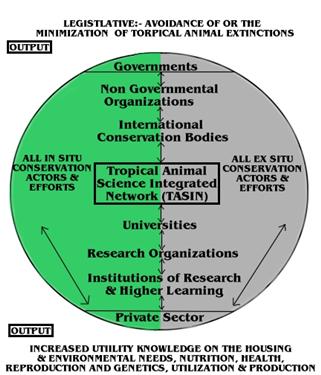

The complementary activity of the in situ and ex situ conservation techniques will pose the new challenges for Tropical Animal Science [TAS]. The major challenges will lie in the intensification of production activities in both the in situ and ex situ conservation situations. It is for this reason that a Tropical Animal Science Integrated Network (TASIN) is being suggested as a component of the OSTAS&P. It is envisioned that this network could be funded and function in a manner similar to the International Board for Plant Genetic Resources (IBPGR). The first task of the OSTAS&P would therefore be to get this network going by any means necessary. The nature of the network linkages and the general expected outputs are presented in Figure 1. This would afford a better opportunity for the two conservation camps to interface and have constructive dialogue with all the stakeholders in Tropical Animal Science, [Domestic Livestock (Food, companion and Laboratory Animals/ animals at different points in the productivity and utility to humanity continuum); animals on the verge of Domestication; and wild Animals]. TASIN was first suggested by Garcia (1999).

The future horizons for Tropical Animal Science and Production lies:

[1]

in getting a better understanding of this wide range of under-utilized non-domesticated tropical animal resources and

[2]

in creating synergisms from the efforts of the 2300 Zoos world wide [the ex situ conservation and research efforts] and the 4000 plus nature reserves worldwide [the in situ conservation efforts].

This work has already started through the initiatives of Darwin, and with the formation of societies such as the London Zoological Society in 1828 and the Smithsonian Institution. These institutions have laid the groundwork for Tropical Animal Science which is still in its infancy as we know it today both in the developed and developing countries. This is because those persons who have been working in Animal Science in the tropics have focused mainly on the exploitation of Dairy and Beef Cattle (Bos Taurus/ B. indicus) for beef and milk, sheep and Goat (Ovia aries and Capra hircus) for mutton, chevron and milk; chickens (Gallus domesticus) for eggs and meat; turkeys (Melagris gallapavo) for meat and plumage; Ducks (Anas platyrhynchos) for meat; Horses (Equus caballus) for work and employment, Dogs (Canis familiaris) and Cats (Felis catus) for companionship. Thus Animal Science has focused mainly on 10 species of animals.

In order for Tropical Animal Science to fully blossom, 'blinkers' would have to be removed; our Eurocentric approach to Animal Science would have to be changed and greater dialogue between the in situ and ex situ approaches to animal conservation management and production must be engaged. Blaut (1997) has suggested that this "Eurocentric diffusionism" has contributed to the current lack of success and overall development of tropical agriculture and has contributed to the destruction of small holder agriculture in Peurto Rico and the United States Virgin Islands. One should take note of this and avoid it having a negative effect on the future of Tropical Animal Science that is still in its infancy. Hence those who subscribe to the thinking of "The Open School of Tropical Animal Science and Production [OSTAS&P]" would agree that there is a need to view Tropical Animal Science and Tropical Livestock Develpment from a different perspective, if the science is to be advanced. A move possibly from "Dialectical" thinking to "Trialectical thinking (critical thinking in the light of advancing the humanizing project)" as has been suggested by the late Dr. Herb Addo in the last paper he wrote (Addo 1996).

This new horizon first begins with the need for the resolution of the conflicts between the following:

Neo Tropical Wildlife conservation

Neo Tropical Wildlife Production

Neo Tropical Wildlife Utilization and Cuisine.

This would require the Harmonious Coordination and collaboration among all stakeholders with a clear unemotional articulation of their respective points of view and The Synergism of Neo-tropial Willife conservation, Production, Utilization and Cuisine.

The TASIN as earlier suggested could be used as the mechanism to achieve this. This approach is based on the philosophy of the Open School of Tropical Animal Science and Production [The St. Augustine School of Tropical Animal Science and Production].

DOMESTICATION

All the domestic animal species that are of importance in the Caribbean and Latin America (the Neo-tropics), with the exception of the Turkey (Melagris gallapavo) and the Muscovy duck (Carina moschata), have been introduced animal species. Enormous amounts of resources and research have been directed towards improvements in the productivity and the understanding these animals (from Europe and Asia), while little or no attention has been given to our indigenous and adapted Neo-tropical wild animal species. In Trinidad & Tobago these indigenous wild animal species that are of importance for conservation, and has the potential for domestication, include the following:

Agouti (Dasyprostya aguti

now D. leporine),

Alligator/ spectacled caiman (Caiman crocodiles/

Caiman sclerops),

Cocrico (Ortalis ruficauda), [this is one of the

two national birds of Trinidad and Tobago],

Deer/ red brocket deer (Mazama

Americana),

Iguana (Iguana iguana),

Lappe/ spotted paca (Agouti

paca),

Manicou/ black eared opossum (Didelphis marsupialis insularis),

Tattoo/ nine banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus), and

Wild hog/

quenk/ collared peccary (Tayassu tajuacu).

Capybara (Hydrochaerus

hydrochaeris) and

Muscuvy Duck (Carina moschata)

Fulvus

Whistling-Duck (Dendrocygna bicolor).

On the other islands of the

Caribbean other useful species include the Mountain Chicken (Leptodactylus

fallax) in Dominica; the Jamaican Rock Iguana (Cyclura collie) and

the Bahamian and Jamaican Hutia (Geocapromys brownii). These latter two

are on the world list of endangered species.

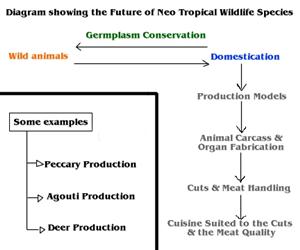

THE FUTURE OF NEO-TROPICAL WILDLIFE SPECIES